PART 2 | 23 OCTOBER – 13 NOVEMBER 2021

Parts of Article I have been borrowed from the Swiss and American constitutions and adapted to European standards.

The first two Clauses of this Article 1 establish the relationship between the federal body, the Member States, and the citizens.

Clause 1 states that the federation is created by the Member States and the Citizens. Thus, the Constitution belongs not only to the Member States but also to the Citizens. They have an independent mandate which is further discussed in Article VII. Mind you: the ratification of the federal constitution by the Citizens is the most far-reaching example of direct democracy.

Clause 1 also stipulates that the federation consists of two layers: that of the federal body with a limited range of powers for common interests and that of the Member States which retain sovereign decision-making powers for all their own interests. Member states do not transfer powers – which means they do not transfer parts of their sovereignty to the federal body but allow that body to share in their sovereignty by making a vertical separation of powers. For a good understanding of this concept of shared sovereignty by the vertical separation of powers I refer to Chapter 5 of the ‘Constitutional and Institutional Toolkit for Establishing the Federal United States of Europe’: https://www.faef.eu/wp-content/uploads/Constitutional-Toolkit.pdf.

The federal body has no authority to interfere in the internal order of Member States. This is a fundamental difference from the European Union, which can use binding directives to force the Member States to adapt their legislation and internal order. The European Union calls this integration, but in reality it is assimilation. The federation of the United States of Europe leaves the Member States as they are and serves only the common interests of those Member States.

Clause 2 makes it unnecessary to include the principle of subsidiarity in the constitution in so many words. The vertical separation of powers is subsidiarity set in stone: the Member States have their own inviolable range of powers, over which the federal body has no control. The federal body has no discretionary - let alone arbitrary - powers to impose on member states what they may or may not regulate or realise.

Let me give an example of how this worked in America after the Paris Climate Accord was reached in December 2015. President Trump refused to sign it. But the state of California did. Preserving the sovereignty of member states of a federation is one of the essences of federal statehood and stands in stark contrast to the Treaty of Lisbon, which in a number of places offers great openings for violating the principle of subsidiarity.

The Clauses 3 and 4 lay down the rights of European Citizens. Instead of including fundamental rights in the form of a Bill of Rights in the constitution, we decided in Clause 3 to link the constitution to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. And to the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. The way in which this link is to be made is a matter that must be settled by means of transitional law after the federal constitution has been adopted.

There is one comment to be made here. The members of the Citizens' Convention are asked to pay attention to a legislative issue in Clause 3. Article 20 of the 'Treaty on European Union' (one of the two partial treaties of the Treaty of Lisbon) gives at least nine Member States the right to establish a form of enhanced cooperation. In our view, this enhanced cooperation could be a federal state that joins the European Union as a member and works to enlarge the federation from there. Article 20 stipulates that the members of such an enhanced cooperation have the right to use the institutions of the EU. For example, the European Court of Justice, the European Central Bank, the European Court of Auditors. If this view is correct, i.e. if nine Member States have the right to create an enhanced cooperation in the form of a federation, then perhaps Clause 3 would be superfluous. After all, the aforementioned European Convention and Charter would automatically fall within the jurisdiction of the federation. A further analysis of this issue - and possibly an amendment to Clause 3 - would be appreciated.

Clause 4 is an additional point concerning those rights. It must be constitutionally established that Citizens have the right to free access to government documents. This is, incidentally, subject to further regulation in an Open Access to Public Documents Act.

Article I – The Federation and the Bill of Rights

- The United States of Europe is formed by the Citizens and the States, participating in the Federation.

- The powers not entrusted to the United States of Europe by the Constitution, nor prohibited to the States by this Constitution, are reserved to the Citizens or to the respective States.

- The United States of Europe accedes to the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, and to the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

- The articles in both Charters on freedom of expression and the freedom of the press also include the freedom to acquire and receive information and also to otherwise provide oneself with the expressions of others. These freedoms are covered by the Open Access to Public Documents Act, which contains provisions on the right of access to public documents.

The following Explanatory Memorandum to the draft federal constitution for the United States of Europe was originally written by Leo Klinkers and Herbert Tombeur in their European Federalist Papers (2012-2013): https://www.faef.eu/the-european-federalist-papers/

Explanation of Clause 1

Here we take inspiration from the American and Swiss Constitutions. The text of the first Clause defines the specific nature of a public federation: it consists not only of States, but also and especially of their Citizens; a Federation is of the Citizens and of the States. For all those who fear that a Federation, as a purported superstate, would absorb the sovereignty of the participating nation states, it should now be clear that within the United States of Europe the States remain: France remains France, Estonia remains Estonia, Spain remains Spain, et cetera.

And there is more: by explicitly naming the Citizens as co-owners of the Federation, there is a constitutional mandate to consult them on proposed changes to the territory of the Federation. A right that the European Citizens have not yet received under the Lisbon Treaty: a form of direct democracy. We address this right in Article VII of our draft.

The States are represented alongside the Citizens at the federal level of government. Their representatives have an individual mandate. They do not act in the name and on behalf of the political institutions of their State. This important principle in the functioning of the Federation is addressed in the organisation of the European Congress consisting of two Chambers.

110 The following Explanatory Memorandum to the draft federal constitution for the United States of Europe was originally written by Leo Klinkers and Herbert Tombeur in their European Federalist Papers (2012-2013): https://www.faef.eu/the-european-federalist-papers/

Explanation of Clause 2

Immediately after the American Constitution came into force, the need for a Bill of Rights became apparent. This came in the form of ten Amendments to the Constitution. Amendments 1-9 contained the fundamental rights themselves. So, we have now incorporated them into Article I, Section 3. The Tenth Amendment (proposed by James Madison and adopted on 15 December 1791) had a different, more state- like character, by explicitly reaffirming the federal state system. We think it is important to record this here in Clause 2 of Article I. It makes clear that the European Federation has a non-hierarchical vertical division of powers. Both the Federal and Member State authorities are sovereign in those matters assigned by the Constitution to both levels of government. In the sense that the Federation is assigned powers for a number of limited policy areas, no others. For lovers of historical best practice from the end of the 18th century, this principle of the vertical separation of powers was already laid down in the first ten days of the Philadelphia Convention and further elaborated in a draft Constitution a few weeks later. It constitutionally establishes that the Federal Authority cannot exercise any hierarchical power over the States.

Those familiar with the Treaty of Lisbon, and more specifically with the partial treaty under the name 'Treaty on European Union', may ask 'What's new'? After all, that Treaty on European Union stipulates in Article 4(1): 'In accordance with Article 5, powers not conferred on the Union in the Treaties shall be conferred on the Member States'. This looks like two drops of water on our Article I, Clause 2.

But appearances can be deceptive. The subsequent Article 5 of that Treaty states that the delimitation of the Union's competences is governed by the principle of conferral. There are two aspects to this principle:

o Whether the Union has power to act is determined by the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality; that is to say, in short, the Union may act decisively in cases which the Member States themselves (or their component parts) could not (better) take care of; in other words, the principle of subsidiarity (leave to the States what the States themselves can best do) is not absolute, but relative.

o In the other part of the Lisbon Treaty - namely the 'Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union' - there are some articles that give a concrete list of the competences of the Union. But those articles are partly hierarchical in character, especially in the group of shared competences - these are competences allocated to both levels of government, but where the Union, when acting, obliges the Member States to conform to them. This does not exist in a Federation.

As if all this were not enough, there are also subsidiary competences available to the Union, granted in Article 352 of the same 'Treaty on the Functioning of the EU'. This means that the Union can act if this is necessary to achieve an objective in the Treaties and if no other provision in the Treaty provides for measures to achieve it. This is called 'the flexible legal basis'. In our view, this is a manipulative and arbitrary key that fits every lock. Apparently, the European Union cannot to this day abandon the technique of invoking the goal of 'ever-increasing integration' in order to seize power when it suits it.

Why does this not even remotely resemble federalisation? Let us discuss it again. Practice has shown for years that the principle of subsidiarity leaks badly. The Protocol preventing the Union from arbitrarily taking decisions outside the realm of its expressly granted competences, including the watchdog role of national parliaments in ensuring compliance with that Protocol, was already working very badly before the advent of the Lisbon Treaty. It has not worked at all since the entry into force of that Treaty in 2009, because from then on, the European Council took over principled decision-making. And nobody can stop that machine. Why is that? Because of the hierarchy we mentioned above: something once decided by the European Council means the obligation for the Member States to implement it uniformly in their own country: the source of assimilating integration. Not only is this alien to a federal system, but it is also unclear who is exclusively competent in what matters. It does say a few times that this or that authority has exclusive competence, but Articles 1 to 15 of the 'Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union' contain so many vague additions that there is no clarity, as there is in the American Constitution.

The US Constitution does not provide that the Federal Authority can overrule the Member States. It confers on the Federal Authority an exhaustively enumerated set of powers and that is all. There is no hierarchy towards the Member States, nor any division of powers. Just like in the Swiss Constitution.

This is the essence of federalism: a true federation has shared sovereignty but not shared powers: each, the Federal Authority, and the Member States, has its own powers. This is the result of the first two weeks of debates in the Philadelphia Convention that began in late May 1787. The 'Virginia Plan', which James Madison had put on the table as the federalist opening piece, contained a Clause giving the federal authority the power to overrule 'improper laws' of states. There was an objection to this, made explicit in the 'New Jersey Plan' produced immediately afterwards. The parties subsequently resolved this dispute in the 'Great Compromise' by opting for a vertical separation of powers, expressed in a series of limitable powers of the federal authority: no hierarchy. Thus, no intervention from above if a member state performs its legislative or executive functions 'improperly'.

That's how it should be: in a federal system, the Member States are and remain sovereign in their own circles. Our Constitution therefore does not mention the principle of subsidiarity at all, for the simple reason that the exhaustive enumeration (more on this later) of federal competences establishes subsidiarity in an absolute sense. The Federal Authority has no discretionary powers - let alone arbitrary powers - to determine for itself what Member States would not be able to regulate or achieve by themselves.

Explanation of Clause 3

The United States of Europe accede to two charters. One is the European Convention or the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, drafted by the European Court of Human Rights. The other is the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

Because both Charters together have a perfectly ordered system of fundamental rights for Citizens within the EU and other European Citizens, not living in the EU (yet), we embrace both Charters as an extended Bill of European Rights. In the fourth paragraph of Clause 3, we add an additional safeguard: the right of Citizens and Press to free access to documents of the federal government, though subject to further provisions in a law.

The reason for embracing the articles of the Charters but not the reference to the principle of subsidiarity is thus – as explained earlier - that the structural dysfunctionality of that principle has allowed the EU to continue its assimilationist production for years, continuing the tradition since the founding of the European Communities. Let us also put it another way: the principle of subsidiarity as enshrined in the European treaties from the outset has never worked in the sense in which it was intended, namely, to leave to the Member States what they themselves do best. When it suits the European Council, it is always bypassed. Only by giving the European federal authority a limitative set of powers (as the Germans say, a 'Kompetenz Katalog') can the disregard for the principle of subsidiarity be stopped.

We are wrestling with a legislative issue here. It has to do with Article 20(2) of the 'Treaty on European Union' (one of the parts of the Lisbon Treaty): this article states that nine Member States are entitled to enter into enhanced cooperation. However, this is only permitted when it promotes the objectives of the EU, protects its interests, and strengthens its integration process. It must not undermine the internal market: a single market for goods, services, persons, and capital.

The relevant provisions of the Lisbon Treaty (including Articles 326 to 334 of the other Lisbon Treaty, the 'Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union') indicate that if the nine EU Member States create a closer partnership (for example, in the form of a Federation) then they may use the Union's institutions. Including everything that exists in terms of regulation around those institutions. Strictly speaking, this would imply, at least that is our interpretation of Article 20 of the 'Treaty on European Union', that after ratification of the Federal Constitution by the peoples of at least nine EU-Member States, that federation would have legal access to all existing EU institutions and their powers. So, also to the European Central Bank, the European Court of Justice and so on.

If this is correct reasoning - a matter for assessment by the Citizens' Convention - then Clause 3 would be superfluous. After all, the Charter of Fundamental Rights would then already apply by law to the Federation of Europe. And then an explicit reference to it in Article 1(3) would not be necessary.

Article I – The Federation and the Bill of Rights

- The European Federal Union is formed by sovereign Citizens and States, participating in the Federation.

- The powers not entrusted to the European Federal Union by the Constitution, nor prohibited to the States by this Constitution, are recognised powers of the Citizens and entrusted powers of the States, in order to protect the autonomous initiatives of Citizens and States, relating to activities of personal or general interest.

- The European Federal Union sees in the natural rights of every living human being the only source from which agreed rights can be derived, such as formulated in the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, and in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Federal Union, whose rights shall have the same legal value as the Constitution.

- Every Citizen has a right of access to documents of the Federation, States, and local Governments and the right to follow the proceedings of the courts and democratically elected bodies. Limitations to this right may be prescribed by law to protect the privacy of an individual, or else only for extraordinary reasons.

- Subject to the provisions of Article V, Section 1, Clause 8, the European Federal Union may accede and adhere to a World Federation on the basis of an Earth Constitution.

Explanation of Clause 1 – the formal basis

From a formal point of view, the sequence of establishing this constitution is as follows. Citizens of EU and other European states - vested with the right to vote - ratify this constitution by simple majority. It is up to the respective parliaments of those states to decide whether to follow the will of their Citizens. The States that follow the will of their Citizens thus establish the Federal European Union. This Federation has two possibilities of existence. Either alongside the intergovernmental European Union, or as a Federation within that European Union. After all, federal Germany, Austria, and Belgium are already members of the EU.

Explanation of Clause 1 – the philosophical basis

The philosophical basis for Clause 1 is as follows. The Federation is all about the sovereignty of the Citizens, the States and the Federation itself. Sovereignty means the right and obligation to’reign’; not to ‘govern’. This means:

- For Citizens to reign their households based on economic principles to attain prosperity through financial liberty.

- For States to reign their households based on sociologic principles to attain wellbeing through cultural equality.

- For the Federation to reign its household based on judicial principles to attain wellness through morality.

The mutual relationship between the Citizens, the States and the Federation form a idiosyncratic trias politica: independent reigning spaces under the principle of subsidiarity, precisely defined, lest deliberations will produce unintelligeable cacofonic noise. If not, Citizens’ and States’ thougts will be quelled by hierarchical power play. Each of the three entities of that trias politica ‘sui generis’ should have and mind its own business for the sake of subsidiarity. The Federation as a whole needs protection against any (group of) Citizens or States with egoistic financial, cultural or political impulses breaking the complex of values of the Preamble, without which our communities remain or become ‘animalistic’ instead of ‘humanistic’.

There are views that deny or minimise Citizens' own independent and sovereign space for thought and action. However, history has repeatedly proven that Citizens do have their own space, and that the constitution (or documents of the same value) must reflects this. Think of the English Magna Carta of 1215 in which the vassals of King John Lackland made it clear that with his signature he had to respect the inalienable rights of his people, otherwise they would depose him. The Netherlands, with the Placcard of Abandonment of 1581, declared the Spanish King no longer to be their sovereign and were prepared for an 80-year war to win this battle. The French Revolution of 1789 and the Declaration of Independence with which the thirteen British colonies declared their independence in 1776 are also examples of the inalienable right of citizens to free themselves from autocratic rule. After WWII, the Dutch, Portuguese, French, Belgian and British colonies did the same. Most of them by force.

Thus, our federal constitution guarantees the free space of Citizens in various places. First, by placing the ratification of the Federal Constitution primarily in the hands of the Citizens of Europe: the ultimate form of direct democracy. This makes it a constitution of, by and for the Citizens. It is then up to the respective parliaments to decide whether or not to follow the will of the people; if so, Citizens and States are co-owners. Subsequently, this own space of the Citizens is laid down in Section III of the Preamble, which reads:

III. Whereas, finally, without prejudice to our right to adjust the political composition of the federal body in elections, we have the inalienable right to depose the federation's authorities if, in our view, they violate the provisions of points I and II,

Finally, the free space of the Citizens is reflected in the referendums of Article V, in particular the introduction of the decisive referendum of Clause 8 of that Article.

Other views grant no or little free space to the member states of the federation. They see the States’ position as 'only' representing the people. So, limited to an administrative role. In other words, they see the space of the Citizens and of the States as coinciding, as it were, and only see a clear distinction between the space of the States and that of the Federal Authority. We do not follow this line of thinking. Although the States are the representation of their people, they are responsible for their own decision making space for the democratic and functional order of the State. This is confirmed by Article VII, Section 3, Clause 2, reading in the original draft version:

“The United States of Europe wil not interfere with the internal organization of the States of the Federation”

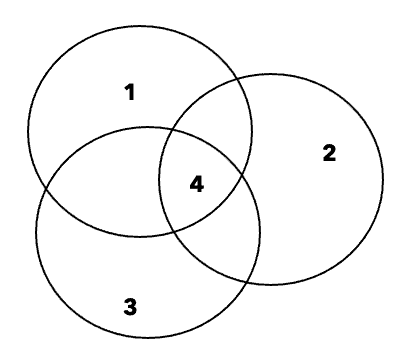

The relationship of these three independent - subsidiary - worlds of thought between the Citizens, the States and the Federation can perhaps be better understood by visualising it with three intersecting circles.

Circle 1 is the world of the reign of the Citizens, Circle 2 of the States and Circle 3 of the Federation, with its horizontal trias politica of legislative, executive and judiciary branches. In the middle - at number 4 - lies the outcome of their combined reigning, expressed in the maximum protection of the complex of values of the Preamble: the ‘holy grail’ so to speak, untraceable but nevertheless obliging to an eternal search by the three entities involved.

Explanation of Clause 1 – the content

From a content point of view, we take inspiration from the American and Swiss Constitutions. The text of the first Clause defines the specific nature of a public federation: it consists not only of States, but also and especially of their Citizens; a Federation is of the Citizens and of the States. They are the co-owners of the federation. For all those who fear that a Federation, as a purported superstate, would absorb the sovereignty of the participating member states, it should now be clear that within the European Federal Union the States remain as they are: France remains France, Estonia remains Estonia, Spain remains Spain, et cetera.

And there is more: by explicitly naming the Citizens as co-owners of the Federation, there is a constitutional mandate to consult them on proposed changes to the territory of the Federation. A right that the European Citizens have not yet received under the Lisbon Treaty: a form of direct democracy. We address this right in Article VII of our draft constitution.

The States are represented alongside the Citizens at the federal level of government. Their representatives have an individual mandate. They do not act in the name and on behalf of the political institutions of their State. This important principle in the functioning of the Federation is addressed in the organization of the European Congress consisting of two Chambers.

Explanation of Clause 2

Clause 2 of Article I makes clear that the European Federation has a non-hierarchical vertical division of powers. This creates ‘shared sovereignty’ between the States and the Federal entity: the States entrust the Federation with the use of some of their powers to look after common interests. These are interests that the States themselves cannot look after (anymore). Entrusting the federal authority with some state powers does not give it any hierarchical power, let alone enable it to intervene in the internal order of the States.

Both the Federal and Member State authorities are sovereign in those matters assigned by the Constitution to both levels of government. In the sense that the Federation is assigned powers for a number of limited policy areas, no others. For lovers of historical best practice from the end of the 18th century, this principle of the vertical separation of powers (not to be confused with hierarchic powers) was already laid down in the first ten days of the Philadelphia Convention and further elaborated in a draft Constitution a few weeks later. It constitutionally establishes that the Federal Authority cannot exercise hierarchical power over the States.

Those familiar with the Treaty of Lisbon, and more specifically with the partial treaty under the name 'Treaty on European Union', may ask 'What's new'? After all, that Treaty on European Union stipulates in Article 4(1): 'In accordance with Article 5, powers not conferred on the Union in the Treaties shall be conferred on the Member States'. This looks like two drops of water on our Article I, Clause 2.

But appearances can be deceptive. The subsequent Article 5 of that Treaty of Lisbon states that the delimitation of the Union's competences is governed by the principle of conferral. This is what should NOT be done; the principle of conferral leaves far too many competence issues indeterminate:

- Whether the Union has power to act is determined by the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality; that is to say, in short, the Union may act decisively in cases which the Member States themselves (or their component parts) could not (better) take care of; in other words, the principle of subsidiarity (leave to the States what the States themselves can best do) is not absolute, but relative.

- In the other part of the Lisbon Treaty - namely the 'Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union' - there are some articles that give a concrete list of the competences of the Union. But those articles are partly hierarchical in character, especially in the group of shared competences - these are competences allocated to both levels of government, but where the Union, when acting, obliges the Member States to conform to them. This does not exist in a Federation.

- As if all this were not enough, there are also subsidiary competences available to the Union, granted in Article 352 of the same 'Treaty on the Functioning of the EU'. This means that the Union can act if this is necessary to achieve an objective in the Treaties and if no other provision in the Treaty provides for measures to achieve it. This is called 'the flexible legal basis'. In our view, this is a manipulative and arbitrary key that fits every lock. Apparently, the European Union cannot to this day abandon the technique of invoking the goal of 'ever-increasing integration' in order to seize power when it suits it.

Why does this not even remotely resemble federalisation? Let us discuss it again. Practice has shown for years that the principle of subsidiarity leaks badly. The Protocol preventing the Union from arbitrarily taking decisions outside the realm of its expressly granted competences, including the watchdog role of national parliaments in ensuring compliance with that Protocol, was already working very badly before the advent of the Lisbon Treaty. It has not worked at all since the entry into force of that Treaty in 2009, because from then on, the European Council took over principled decision-making. And nobody can stop that machine. Why is that? Because of the hierarchy we mentioned above: something once decided by the European Council means the obligation for the Member States to implement it uniformly in their own country: the source of assimilating integration. Not only is this alien to a federal system, but it is also unclear who is exclusively competent in what matters. It does say a few times that this or that authority has exclusive competence, but Articles 1 to 15 of the 'Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union' contain too many vague additions that there is no clarity.

The European Federal Union does not provide that the Federal Authority can overrule the Member States. It confers on the Federal Authority an exhaustively enumerated set of powers and that is all. There is no hierarchy towards the Member States, nor any division of powers. Just like in the Swiss and US Constitution.

This is the essence of federalism: a true federation has shared sovereignty but not shared powers: each, the Federal Authority, and the Member States, has its own powers. This is the result of the first two weeks of debates in the Philadelphia Convention that began in late May 1787. The 'Virginia Plan', which James Madison had put on the table as the federalist opening piece, contained a Clause giving the federal authority the power to overrule 'improper laws' of states. There was an objection to this, made explicit in the 'New Jersey Plan', produced immediately afterwards. The parties subsequently resolved this dispute in the 'Great Compromise' by opting for a vertical separation of powers, expressed in a series of limitable powers of the federal authority: no hierarchy. Thus, no intervention from above if a member state performs its legislative or executive functions 'improperly'.

That's how it should be: in a federal system, the Member States are and remain sovereign in their own circles. Our Constitution therefore does not mention the principle of subsidiarity at all, for the simple reason that the exhaustive enumeration (more on this later) of federal competences establishes subsidiarity in an absolute sense. The Federal Authority has no discretionary powers - let alone arbitrary powers - to determine for itself what Member States would not be able to regulate or achieve by themselves.

Explanation of Clause 3

Immediately after the American Constitution came into force, the need for a Bill of Rights became apparent. This came in the form of ten amendments to the seven-article Constitution. That Bill of Rights subsequently formed an annex to the Constitution. The ten-article federal constitution of the European Federal Union does not contain a Bill of Rights either. It refers to rights that apply by reference to other documents. It is as follows.

The third Clause of Article I sees the rights of European Citizens as deriving from natural rights. Man has no authority over these. Natural rights are fundamental, self-evident rights. And what 'goes without saying' does not need to be explained. In addition to these rights by virtue of nature, we have rights by virtue of agreements made with the consent of all participants. In our modern time these agreements are laid down in Charters because they have a transnational character.

The wording 'every living human being' means that the constitution does not grant natural, fundamental, self-evident rights to every other living being on earth: animals, plants, the seas, and all possible other living, non-human phenomena. Agreed rights are derived from them, but such rights are currently very much under discussion and can be laid down in other documents than the federal constitution.

So, there is a division between natural rights and cultural rights. Natural rights do not need to be formulated, because to do so would be to erroneously state that they are adaptable or negotiable. This is only possible with rights derived from natural law that are laid down by men made agreement in Charters.

Clause 3 refers to Charters for those concrete, men made, cultural rights, without considering the Charters’ various intergovernmental arrangements and references to intergovernmental institutions. It is not necessary, nor advisable to incorporate concrete rights already laid down in Charters literally into the Constitution. This is also to avoid the need to develop new case law and the consequently need to amend the constitution when jurisprudence gives cause to modify these cultural rights. In the event that the EU ceases to exist, the Federation can adopt the Charters - adapted or not - as its own human rights domain.

Post-totalitarian constitutions have always worked like this: they open themselves to international human rights treaties and thanks to these they manage to update the protection of fundamental rights without having to change the text all the time. To pretend to fix an exhaustive list of fundamental rights without referring to the human rights treaties or the Charter of fundamental rights would end up frustrating the need to guarantee a high standard of protection to the rights themselves because the text of the constitutions gets old if it is not linked to the evolution of the international community. The history of constitutional law is full of referrals like this, we need to produce a document that has the ambition to work.If we do not recognise the constitutional value of the Charter of Fundamental Rights, we will undermine the strength of fundamental rights. It will bind lawmakers, but this is what constitutions normally do and this is how the judicial review of legislation works. Courts rely on the constitution to declare the invalidity of pieces of legislation that are seen as in conflict with fundamental rights.

There are many examples of constitutional provisions like this: Art. 10, paragraph 2, of the Spanish Constitution, Art. 16 of the Portuguese Constitution, Art. 5 of the Bulgarian Constitution, Art. 20 of the Romanian Constitution, Art. 93 of the Netherlands, and many others. If this reference is ignored we should write a detailed list of rights and this would make the constitutional text much longer, whereas one of the objectives is to draft a short, effective, and comprehensible text. So, this explains why it is not necessary, nor advisable to incorporate concrete rights already laid down in Charters literally into the Constitution.

The constitution - once ratified - binds everyone: individuals, governments, and private organisations of all kinds. Therefore, it is not necessary to require a signature from Citizens and organizations to confirm commitment to the constitution. That is implicitly established. The reason to mention it explicitly here is the circumstance that there are always individuals or organisations that violate human rights. With the third Clause of Article I, it is clear that the European Federal Union is a secular republic that unconditionally opposes the violation of human rights by any person or institution.

Explanation of Clause 4

The freedom of information and transparency is so fundamental and vital for democracy and legitimacy/public trust in authorities, that it deserves to be included directly right there in Article I.

Explanation of Clause 5

Clause 5 establishes constitutionally that the Federation Europe sees itself as one of the building blocks of a World Federation. Only if the Earth is governed by a World Federation, supported by a number of (continental) federal states such as the European Federal Union, can geopolitically tensions, armed conflicts, and greed - causes of unprecedented human suffering (destruction of the earth, refugees, torture, migration flows, poverty, disease, illiteracy and more) - be overcome.

All Clauses of Article I have the hallmark of establishing fundamental commitments. If we ask for commitment from EU Member States to sign up as members of a federal Europe, then a World Federation may ask for commitment from a federal Europe to act as one of the building blocks of the foundation of that World Federation.

Just as our constitutional federal Europe must replace the undemocratic intergovernmental EU system, so a constitutional World Federation must replace the UN's dysfunctional system of treaties.

Clause 5 makes it clear that it is indeed the Citizens of the European Federal Union who (must) take such a decision. This is stated in Article V, Section 1, Clause 8: the President shall organise a decisive referendum among all citizens on such affiliation/adherence.