DEL 4 | 4 DECEMBER 2021 – 15 JANUARY 2022

Indholdet af artikel III forklarer, hvad der menes med den vertikale adskillelse af beføjelser mellem medlemsstaterne og det føderale organ. Fordi medlemsstaterne har fælles interesser, som de ikke kan forsvare alene, overlader de nogle af deres beføjelser til et forbundsstatsorgan. De overdrager ikke deres beføjelser, men gør dem så at sige hvilende. Deres suverænitet forbliver uberørt. Det føderale organ varetager staternes fælles interesser med staternes beføjelser. Hvis det føderale organ forvalter staternes beføjelser forkert, bliver denne "hvilende" magt tilbageført, fordi føderationen - i henhold til forfatningens artikel I - er borgernes og staternes ejendom.

Artikel III handler hovedsagelig om den udtømmende liste over det føderale organs beføjelser til at fremme medlemsstaternes fælles interesser. Bemærk godt: Præamblen handler om værdier, artikel III handler om, hvordan føderationen vil forsøge at sikre disse værdier.

Afdeling 1 er vigtig for føderationens indtægter. Borgernes Hus kan vedtage skattelove, mens Senatet kan fremsætte forslag til ændring af dem: kontrol og balance.

Begge kamre kan udarbejde føderale love. Dette adskiller sig betydeligt fra, hvad der er sædvanligt i de fleste lande. Her er det regeringerne, der udarbejder lovforslag, og parlamenterne er de organer, der vedtager eller ændrer dem. Denne magt, som den lovgivende forsamling har til selv at udarbejde lovforslag, tvinger præsidenten til at acceptere dem til gennemførelse eller ej. Hvis ikke, finder der en proces med argumenter og modargumenter sted, hvor antallet af stemmer i den lovgivende forsamling i sidste ende afgør, hvem der vinder.

Afdeling 2 i artikel III er en udtømmende liste over kongressens beføjelser. Hvad præsidenten som leder af den udøvende magt kan gøre med den, er anført i artikel V om præsidentens beføjelser. Det vil jeg komme ind på senere.

Igen: Præamblen indeholder de værdier, som føderationen ønsker at bevare, og artikel III, stk. 2, handler om listen over lovgivers begrænsende beføjelser til at beskytte disse værdier. Denne liste handler altså ikke om politik, f.eks. om at reducere CO2 for at beskytte klimaet. At den lovgivende magt kan føre politik på dette punkt fremgår af afsnit 2, litra g: "at regulere og håndhæve regler for at fremme og beskytte klimaet og kvaliteten af vand, jord og luft". Men det er op til medlemmerne af den europæiske kongres at beslutte, hvad indholdet af denne politik skal være. Forfatningen er ikke venstreorienteret, ikke højreorienteret, ikke progressiv, ikke konservativ. Den danner grundlaget for at sætte en politisk kurs med politiske foranstaltninger. Men det er medlemmerne af Borgernes Hus og Senatet, der bestemmer, hvad disse politikker skal være.

Medlemmer af 55+-gruppen, der ønsker at stille ændringsforslag til sektion 2, anmodes om at anvende dette abstraktionsniveau. Et ændringsforslag i stil med: "USE reducerer CO2-emissionerne med 50% inden år XX" er ikke hensigtsmæssigt. Det er politik og hører ikke hjemme i en forfatning.

Endnu en gang. Forfatningen har ingen politisk farve. Den er det "fælles hus", som vi alle skal bo i, hvor vi alle skal søge lykke, velstand og frihed så vidt muligt. Hvis vi opbygger en forfatning baseret på specifikke politikker, vil vi let kunne tiltrække personer, organisationer og partier, der går ind for disse specifikke politikker, men vi vil miste støtten fra alle andre personer, organisationer og partier. En føderal forfatning må ikke være en socialistisk forfatning, den må ikke være en kristdemokratisk forfatning, den må ikke være venstreorienteret eller højreorienteret eller hvad som helst. Det er en forfatning for alle europæiske borgere og for alle europæiske lande og regioner. Og det skal udtrykkes i forfatningsretlige ord. Ikke i ord om politik og politikker.

I afsnit 3, første paragraf, hedder det, at de enkelte staters indvandringspolitik vil blive udfaset og blive et føderalt anliggende efter XX år. Det implicitte forbehold, at medlemsstaterne først kan føre deres egen indvandringspolitik i et stykke tid, stammer fra den tid, hvor der endnu ikke fandtes en traktatbaseret fælles EU-politik. Det er derfor en god bestemmelse at ændre i den forstand, at indvandringspolitik fra starten er et anliggende for føderale myndigheder.

Afsnit 4 og 5 indeholder bestemmelser om begrænsning af beføjelser. I afsnit 5 indeholder paragraf 4-9 strenge bestemmelser til forebyggelse af politisk korruption. Påvirkning af valg og politik med penge skal være udelukket.

Artikel III - Den lovgivende magts beføjelser

Afdeling 1 - Fremgangsmåde til at lave love

- Borgernes Hus har beføjelse til at tage initiativ til skattelove for Europas Forenede Stater. Senatet har beføjelse til - som det er tilfældet med andre lovinitiativer fra Borgernes Hus - at foreslå ændringer med henblik på at justere de føderale skattelove.

- Begge kamre har beføjelse til at tage initiativ til love. Hvert lovforslag fra en af kamrene forelægges for præsidenten for De Forenede Stater i Europa. Hvis han/hun godkender lovforslaget, underskriver han/hun det og sender det til det andet hus. Hvis præsidenten ikke godkender lovforslaget, sender han/hun det med sine indvendinger tilbage til det parlament, der har taget initiativ til lovforslaget. Parlamentet noterer præsidentens indvendinger og fortsætter med at tage udkastet op til fornyet behandling. Hvis to tredjedele af Parlamentet efter en sådan fornyet behandling er enige om at vedtage lovforslaget, sendes det sammen med præsidentens indvendinger til det andet Parlament. Hvis denne forsamling godkender lovforslaget med to tredjedeles flertal, træder det i kraft som lov. Hvis et lovforslag ikke returneres af præsidenten inden for ti arbejdsdage efter at være blevet forelagt ham/hende, træder det i kraft, som om han/hun havde underskrevet det, medmindre kongressen ved udsættelse af sine aktiviteter forhindrer, at det returneres inden for ti dage. I så fald bliver det ikke til lov.

- Enhver ordre, beslutning eller afstemning, bortset fra et lovforslag, der kræver begge kammeres samtykke - bortset fra beslutninger om udsættelse - forelægges for formanden og skal godkendes af ham/hende, før de får retsvirkning. Hvis formanden ikke godkender det, får sagen alligevel retsvirkning, hvis to tredjedele af begge kamre godkender den.

Afdeling 2 - De materielle beføjelser for Den Europæiske Kongres' kamre

Den Europæiske Kongres har magten:

- at pålægge og opkræve skatter, afgifter og punktafgifter til betaling af De Forenede Stater Europas gæld og til dækning af de udgifter, der er nødvendige for at opfylde garantien som beskrevet i præamblen, idet alle skatter, afgifter og punktafgifter er ensartede i hele De Forenede Stater Europas område;

- at låne penge på Europas Forenede Staters kredit;

- at regulere handelen mellem de europæiske stater i De Forenede Stater og med fremmede nationer;

- at regulere ensartede indvandrings- og integrationsregler i hele Europas Forenede Stater, og at disse regler skal opretholdes i fællesskab af staterne;

- at fastsætte ensartede regler om konkurs i hele Europa og USA;

- at udmønte den føderale valuta, regulere dens værdi og fastsætte vægt- og målestandard; at fastsætte bestemmelser om straf for forfalskning af værdipapirer og valuta i De Forenede Stater i Europa;

- at regulere og håndhæve reglerne for at fremme og beskytte klimaet og kvaliteten af vand, jord og luft;

- at regulere produktionen og distributionen af energi;

- at fastsætte regler til forebyggelse, fremme og beskyttelse af folkesundheden, herunder erhvervssygdomme og arbejdsulykker;

- at regulere enhver form for trafik og transport mellem forbundsstaterne, herunder den tværnationale infrastruktur, postfaciliteter, telekommunikation samt elektronisk trafik mellem offentlige forvaltninger og mellem offentlige forvaltninger og borgere, herunder alle nødvendige regler til bekæmpelse af svig, forfalskning, tyveri, beskadigelse og ødelæggelse af postale og elektroniske oplysninger og deres informationsbærere;

- at fremme udviklingen af videnskabelige resultater, økonomiske innovationer, kunst og sport ved at sikre forfattere, opfindere og designere eneretten til deres frembringelser;

- at oprette føderale domstole, der er underlagt Højesteret;

- at bekæmpe og straffe pirateri, forbrydelser mod folkeretten og menneskerettighederne;

- at erklære krig og fastsætte regler for fangster til lands, til vands eller i luften; at oprette og støtte et europæisk forsvar (hær, flåde, luftvåben); at oprette en milits til at gennemføre føderationens love, undertrykke oprør og afvise angribere;

- at vedtage alle love, der er nødvendige og hensigtsmæssige for at gennemføre gennemførelsen af ovennævnte beføjelser og af alle andre beføjelser, der i henhold til denne forfatning er tillagt Europas Forenede Staters regering eller et ministerium eller en embedsmand i denne.

Afsnit 3 - Garantier for enkeltpersoners rettigheder

- Indvandring af personer fra stater, der anses for at være tilladt, er ikke forbudt af den europæiske kongres før år 20XX.

- Retten til habeas corpus suspenderes ikke, medmindre det anses for nødvendigt af hensyn til den offentlige sikkerhed i tilfælde af oprør eller invasion.

- Den Europæiske Kongres har ikke lov til at vedtage en lov med tilbagevirkende kraft eller en lov om borgerlig død. ej heller vedtage en lov, der forringer kontraktlige forpligtelser eller retsafgørelser fra en hvilken som helst domstol.

Afsnit 4 - Begrænsninger for Europas Forenede Stater og deres stater

- Der opkræves ingen skatter, afgifter eller punktafgifter på grænseoverskridende tjenesteydelser og varer mellem staterne i De Forenede Stater i Europa.

- Der vil ikke ved nogen form for regulering blive givet fortrinsret til handel eller beskatning i sø- og lufthavne i de europæiske stater i De Forenede Stater, og skibe eller luftfartøjer, der er på vej til eller fra en stat, vil ikke blive tvunget til at anløbe, klare eller betale told i en anden stat.

- Ingen stat må vedtage en lov med tilbagevirkende kraft eller en lov om civil død. Ej heller vedtage en lov, der forringer kontraktlige forpligtelser eller retsafgørelser fra en hvilken som helst domstol.

- Ingen stat vil udstede sin egen valuta.

- Ingen stat vil uden Den Europæiske Kongres' samtykke pålægge nogen form for skat, afgift eller punktafgift på indførsel eller udførsel af tjenesteydelser og varer, bortset fra hvad der måtte være nødvendigt for at gennemføre kontrol af indførsel og udførsel. Nettoudbyttet af alle skatter, afgifter eller punktafgifter, som en stat pålægger import og eksport, vil være til brug for Europas Forenede Staters finansforvaltning; alle dertil knyttede bestemmelser vil være underlagt revision og kontrol af den europæiske kongres.

- Ingen stat må uden Den Europæiske Kongres' samtykke have en hær, en flåde eller et luftvåben, indgå en aftale eller pagt med en anden stat i Føderationen eller med en fremmed stat eller deltage i en krig, medmindre den faktisk er invaderet eller står over for en overhængende trussel, der udelukker udsættelse.

Afsnit 5 - Begrænsninger for Europas Forenede Stater[1]

- Der må ikke trækkes penge fra statskassen, medmindre de anvendes til det formål, der er fastsat i forbundslovgivningen; der vil hvert år blive offentliggjort en redegørelse om Europas Forenede Staters finanser.

- Europas Forenede Stater vil ikke tildele nogen adelstitel. Ingen person, der under Europas Forenede Stater har et offentligt eller betroet embede, må uden den europæiske kongres' samtykke acceptere nogen gave, belønning, embede eller titel af nogen art fra nogen konge, prins eller fremmed stat.

- Intet personale, betalt eller ulønnet, fra regeringen, offentlige kontrahenter eller enheder, der modtager direkte eller indirekte finansiering fra regeringen, må sætte foden på fremmed jord med henblik på fjendtligheder eller handlinger til forberedelse af fjendtligheder, medmindre det er tilladt i henhold til en krigserklæring fra Kongressen.

- Ingen person eller enhed, hvad enten den er levende, robot eller digital, må bidrage med mere end en dagsløn for en gennemsnitlig amerikansk arbejder til en person, der søger et valgt embede i en bestemt valgperiode, i form af valuta, varer, tjenesteydelser eller arbejdskraft, uanset om det er betalt eller ulønnet. Enhver, der søger en valgt stilling, og som accepterer mere end dette beløb i nogen form, og enhver, der forsøger at omgå denne lovbestemte grænse for kampagnebidrag, vil blive udelukket fra at bestride et embede på livstid og vil blive idømt en fængselsstraf på mindst fem år.

- Ingen person eller enhed, der direkte eller indirekte har modtaget midler, begunstigelser eller kontrakter fra regeringen i de seneste fem år, må bidrage til en valgkampagne under de sanktioner, der er beskrevet i stk. 6. Desuden skal enhver enhed, der forsøger at omgå denne begrænsning, idømmes en bøde svarende til fem år af sin årlige omsætning, som skal betales ved domfældelse.

- Ethvert bidrag, hvad enten det er direkte eller indirekte, i form af kontanter, varer, tjenesteydelser eller arbejdskraft, betalt eller ulønnet, til en person, der søger et valgt embede, skal offentliggøres senest 48 timer efter modtagelsen. Bidraget fra hver enhed skal være forsynet med navnet på den eller de personer, der er ansvarlige for ledelsen af enheden. En enhed, der forsøger at omgå denne begrænsning, straffes med en årlig bøde på fem år, der skal betales ved domfældelse.

- Ingen person må bruge mere end en måned af gennemsnitsarbejderen gennemsnitlige månedsløn på sin egen kampagne til et valgt embede. Enhver, der ønsker at omgå denne lovbestemte grænse for kampagnebidrag, vil blive udelukket fra at bestride et embede på livstid og vil blive idømt en straf på mindst fem års fængsel.

- Ingen statsansat må acceptere en stilling i en privat virksomhed, der har accepteret statslig finansiering, begunstigelser eller kontrakter i en periode på ti år efter at have forladt det statslige embede inden for de seneste fem år.

- Alle offentlige institutioner og agenturer og alle enheder eller personer, der direkte eller indirekte har modtaget offentlig finansiering, begunstigelser eller kontrakter, skal underkastes en uafhængig revision hvert fjerde år, og resultaterne af disse retsvidenskabelige revisioner skal offentliggøres på datoen for deres udstedelse. Enhver enhed, der forsøger at omgå eller undgå dette krav, vil blive idømt en bøde på fem års fængsel, der skal betales i tilfælde af en domfældelse. Enhver person, der forsøger at omgå eller undgå dette krav, skal afsone en fængselsstraf på mindst fem år.

[1] Klausulerne 3-9 i artikel III blev tilføjet af Leo Klinkers, som er hentet fra Charles Hugh Smith, 10 fornuftige ændringer til den amerikanske forfatning, 21. februar 2019.

Kongressens beføjelser vedrører spørgsmål af national betydning. F.eks. valuta, føderale skatter, handelsforbindelser med andre lande, udenrigsanliggender og forsvar. Og en række andre - udtømmende opregnede - anliggender.

Hvert lovforslag kommer altså fra et af kamrene og forelægges først for præsidenten. Han kan enten underskrive det eller nedlægge et begrundet veto. I sidstnævnte tilfælde går det tilbage til det pågældende hus til fornyet behandling. Hvis dette hus og det andet hus derefter vedtager forslaget med et flertal på to tredjedele, vedtages loven.

Forklaring til afsnit 1

Her vælger vi en anden struktur end i den amerikanske forfatning. Den amerikanske artikel I i forfatningen har ti sektioner. Disse omhandler både kongressens organisation og dens beføjelser. Vi mener, at det er bedre at opdele disse to emner. Derfor har vi givet vores artikel II titlen "Organisering af den lovgivende forsamling", som så dækker sektionerne 1-6. Derefter behandler vi afsnit 7-10 i en ny artikel III under titlen "Den lovgivende forsamlings beføjelser". Afsnit 7-10 i den amerikanske artikel I er så nummereret som afsnit 1-4 i vores artikel III.

Begge kamre udarbejder altså initiativlove. Ikke præsidenten og hans ministre i hans kabinet. De handler ikke engang i parlamenterne. Denne strenge adskillelse af den lovgivende og udøvende magt garanterer Den Europæiske Kongres' autonomi i sin kerneopgave: udarbejdelse og endelig godkendelse af føderale love.

Afsnit 1 giver Borgernes Hus enekompetence til at udstede skattelove. I modsætning til lovgivning i generel forstand har Senatet derfor ikke denne beføjelse. Senatet kan dog forsøge at ændre disse skattelove gennem ændringsforslag. Begrundelsen for at erklære, at kun Borgernes Hus har kompetence til at tage et initiativ på dette område, er baseret på den betragtning, at det udelukkende og udelukkende er repræsentanterne for borgerne, der har kompetence til at "famle i borgernes pengepung".

Borgernes Hus beslutter således, hvilken form for føderal beskatning der skal finde sted: indkomstskat, selskabsskat, ejendomsskat, vejskat, formueskat, skat på overskud og/eller merværdiafgift. Eller måske overlader det disse former for skat til staternes kompetence og opretter kun en ny form for skat under navnet forbundsskat, forudsat at staternes skatter samtidig nedsættes eller afskaffes for at forhindre, at denne forbundsskat indføres på borgernes bekostning. Vi siger ikke mere om dette, for det er et emne for de politisk valgte. Derfor kommenterer vi her ikke tvisten om harmonisering af skatterne, f.eks. selskabsbeskatning.

I paragraf 2, anvendelsen af den Lex Silencio Positivo, en regel i romersk ret, er bemærkelsesværdig: hvis formanden ikke udtaler sig inden for ti dage, bliver forslaget automatisk lov. Hvis præsidenten forkaster lovforslaget, skal han begrunde sin forkastelse og sende det tilbage til den forsamling, der har udarbejdet det. Dette kaldes præsidentens veto. Ordet "veto" er i øvrigt ikke udtrykkeligt nævnt i den amerikanske forfatning. Det er det heller ikke i vores artikel.

På dette punkt er det nyttigt kort at diskutere en af konsekvenserne af det amerikanske valg om at støtte princippet om trias politica med et genialt system af checks and balances. I praksis fører dette i USA nogle gange til en situation, hvor et af kamrene sammen med præsidenten danner en blokade for at løse en budgetkrise (fiscal cliff). Overfladisk set kunne man tilskrive dette en fejl i det forfatningsmæssige system: Hvis begge magter står på deres forfatningsmæssige linjer, opstår der en blindgyde. Og det kunne man se som en fejl i den amerikanske forfatning. Men denne opfattelse er forkert, hvis man går tilbage til hovedårsagen til, at dette system af checks and balances blev indført: aldrig mere skal nogen være den absolutte chef over alle andre. Det tvinger alle involverede parter til i tilfælde af et eventuelt dødvande at vise det ansvar, som borgerne har givet dem. Og det er hverken mere eller mindre end at sikre, at dødvandet bliver løst. Fortsættelsen af en så trist situation skyldes således ikke en systemfejl i den amerikanske forfatning, men de involverede politikeres manglende evne til at tage ansvar for det fælles bedste.

I det amerikanske præsidentielle system er ingen af de tre grene - den lovgivende, den udøvende og den dømmende magt - chef for den anden. Der er kun én chef: folket. Folket kan demonstrere denne magt på to måder: ved valg og ved en folkeafstemning, der tilbyder en afgørende løsning, når de tre regeringsgrene er gået i hårdknude. Spørgsmålet om folkeafstemning behandles i punkt 6.8.

Forklaring til afsnit 2

Den begrænsende opregning af den føderale myndigheds beføjelser er et typisk træk ved det føderale system: staterne kan regulere alt det, der ikke udtrykkeligt er tildelt den føderale myndighed. Det er præcist fastsat, at forbundsregeringen ikke må blande sig i spørgsmål, der hører under staternes kompetencekompleks. Se her beskyttelsen af staternes suverænitet. Og omvendt er det også fastsat, i hvilken henseende disse stater ikke må gribe ind i den føderale myndighed, medmindre kongressen giver tilladelse hertil.

Her er netop en af de vigtigste forskelle mellem mellemstatslighed og føderation: intet hierarki i toppen, fælles suveræn lovgivningsmagt for føderationen og dens bestanddele, staterne. Altså ingen indblanding i det føderale niveau og i staternes. Dette er i modstrid med den populære misforståelse, at en forbundsstat er en superstat, der bryder sammen og absorberer de enkelte delstaters suverænitet. Quod non. I et føderalt system forbliver staternes og det føderale organs beføjelser adskilt.

Den begrænsende opregning af den lovgivende myndigheds beføjelser har til formål at regulere fælles interesser, som borgerne eller staterne ikke kan varetage. Kernen i den vertikale magtfordeling er, at borgerne og staterne beder et føderalt organ om at varetage en begrænset række fælles interesser (som de også er villige til at betale for), uden at dette føderale organ har ret til at påtage sig, at det er alles chef. Alle andre beføjelser forbliver hos borgerne og staterne og er uantastelige for den føderale myndighed. Staterne beholder deres eget parlament, deres egen regering og deres egen retsmyndighed for det, der ikke er overdraget til Europas Forenede Stater.

Dette afsnit 2 er vores version af det såkaldte "Kompetenz Katalog", som Tyskland foreslog under Maastricht-traktaten i 1992 og mange gange derefter, men som altid blev afvist af de andre EU-lande. Dette er en af de alvorlige mangler ved det mellemstatslige system.

Vores liste er helt anderledes end de udtømmende lister (flertal), som vi finder i traktaten om Den Europæiske Unions funktionsmåde med hensyn til EU. Ikke alene er de ikke præcist og reelt udtømmende, men de er også forpurret af det ukontrollable subsidiaritetsprincip, den hierarkiske udøvelse af beføjelser og kompetencefordelingen, som alle er en forbandelse i et virkelig føderalt tempel, fordi de griber ind i staternes suverænitet. For øvrigt er dette princip om en begrænsende opregning af de føderale beføjelser et af de største resultater af forhandlingerne i Philadelphia-konventet, og det blev opnået i løbet af to uger.

Dette synes at være et godt sted at citere Frank Ankersmit, emeritus professor i filosofihistorie. I den hollandske årbog om parlamentarisk historie 2012 med titlen "Europas Forenede Stater" skriver han bl.a:

"Der er ingen grund til at komme ind på beslutningstagningen i Europa her, og derfor er det tilstrækkeligt at konstatere, at den er i modstrid med alt, hvad der er blevet tænkt på i den politiske filosofis historie om offentlig beslutningstagning. Denne beslutningstagning i Europa er helt unik i historien - og det er bestemt ikke ment i positiv forstand. I betragtning af de enorme problemer med den europæiske forening kan man forstå det, men det er og bliver en grim ting. Mere specifikt er denne beslutningsproces faktisk den officielle kodificering af alle usikkerhederne omkring det endelige mål med den europæiske forening. Det er, som om de europæiske administratorer bevidst har omsat denne usikkerhed til en forvaltningsstruktur, der er det organisatoriske udtryk for den. Det er, som om de ønskede at forankre Europas manglende evne til før eller siden at springe over sin egen skygge i en administrativ struktur, der faktisk ville gøre dette umuligt."

Sammenlign dette med de allerede nævnte systemiske fejl (se kapitel 3) i Lissabontraktaten. Det er et dokument med så mange fejl (lovgivningsmæssigt, demokratisk, organisatorisk og beslutningsmæssigt), at fornyelse kun er mulig ved at træde ud af det: "træde ud af den kasse" og undgå den faldgrube, at man forsøger at forbedre systemet ved at tilpasse den mangelfulde traktat. Den er trods alt fyldt med systemfejl. Enhver ny ændring vil være forgiftet af disse fejl, fordi de så at sige er "genetisk" indbrændt i den.

De ledende personer i det mellemstatslige system er ikke klar over, hvor ødelæggende en forkert lovgivning er for et samfund. Grundlæggende viden og forståelse for behovet for en gennemtænkt forfatningsmæssig udformning som grundlag for et velfungerende samfund er tilsyneladende fraværende. Utilstrækkelig viden og manglende mod til at yde et væsentligt bidrag til skabelsen af Europas Forenede Stater.

At acceptere Lissabontraktaten som grundlaget for bestræbelserne på at skabe et forenet Europa er efter vores mening en form for uønsket relativisering af lovgivningen. Som en bagatellisering af behovet for under alle omstændigheder at sikre, at samfundets forfatningsmæssige grundlag har en professionelt formuleret kodificering. Selv om dele af retten, især forvaltningsretten, har fået en instrumentel funktion (retten som et redskab til at nå politiske politiske mål), er og bliver der doktriner om umistelig, grundlæggende ret, som hverken politik eller politik må pille ved. Retsstatsprincippet betyder, at ingen er hævet over loven. Men det har kun mening, hvis lovgivningen udarbejdes efter uigendrivelige standarder, der ikke er forurenet af politisk folklore.

Nu til vores udkast til den føderale forfatning. De vigtigste tilføjelser i forhold til den amerikanske forfatning er:

- Klausul d, indvandringspolitik som et føderalt anliggende, der ikke længere hører under en europæisk medlemsstat, men med staternes samarbejde om håndhævelse af de føderale regler, f.eks. gennem deres bistands-, uddannelses- og polititjenester.

- Bestemmelse j, grundlaget for en føderal tilgang til en europæisk digital (elektronisk) dagsorden samt bekæmpelse af cyberkriminalitet.

- Paragraf n indeholder bestemmelser om oprettelse af føderale væbnede styrker, dvs. en europæisk hær bestående af landstyrker, flådestyrker og luftstyrker. Et velkendt nationalt(istisk) drevet stridspunkt, men som provinsiel folklore under en føderal forfatning ikke værd at bestride.

Så denne afdeling 2 handler om det vigtigste aspekt af en føderation: den vertikale adskillelse af magten mellem føderationen på den ene side og borgerne og staterne på den anden side. Hvad Den Europæiske Kongres kan regulere, er udtømmende opregnet her. Det betyder dog ikke, at det umiddelbart er klart, hvor mange ministre den udøvende magt skal eller kan bestå af. Så for hvilke politikområder skal der være en minister med sit eget ministerium fra starten af Europas Forenede Stater? Det vil vi tage fat på under organiseringen af den udøvende magt.

I forbindelse med denne udtømmende liste bør der foretages tre sondringer.

For det første skal vi bemærke, at Europas Forenede Stater logisk set også har kompetence til at udøve de beføjelser, som de har fået tildelt, ikke kun inden for Føderationen, men også uden for, f.eks. ved at indgå traktater. Vi forbinder Føderationens beføjelser både med dens interne politik og dens udenrigspolitik. Det samme gælder for de stater, der er medlemmer af føderationen. Hvordan dette fungerer, er beskrevet i den udøvende magts organisation.

For det andet må vi påpege den sidste beføjelse i afsnit 2, paragraf o. I den amerikanske forfatnings tekst står der "At lave alle love, der er nødvendige og hensigtsmæssige for at gennemføre de ovennævnte beføjelser og alle andre beføjelser, der i henhold til denne forfatning er tillagt USA's regering eller et ministerium eller en embedsmand i denne." Dette er den berømte "Necessary and Proper Clause": Kongressen kan lave alle de love, den mener, den har brug for. Men hvis de ikke entydigt udspringer af de begrænsede beføjelser i deres artikel I, afsnit 8 (vores artikel III, afsnit 2), kan præsidenten nedlægge veto mod dem. Eller Højesteret kan erklære dem forfatningsstridige, den såkaldte "Judicial Review". Se kapitel 10.

For det tredje et andet vigtigt aspekt. Den amerikanske kongres har faktisk endnu flere beføjelser end dem, der er nævnt i forfatningen i henhold til artikel I, afsnit 8 (vores artikel III, afsnit 2). Vi bevæger os nu ind på området for de såkaldte "Implied Powers" (se yderligere kapitel 10): beføjelser, der ikke er bogstaveligt nævnt i forfatningen, men som er afledt af kompetencekomplekset i den amerikanske Section 8.

En af de vigtigste kaldes "Kongressens tilsyn". Dette tilsyn - der hovedsagelig foregår gennem parlamentariske udvalg (både stående og særlige), men også med andre instrumenter - vedrører den overordnede funktion af den udøvende magt og de føderale agenturer. Formålet er at øge effektiviteten og produktiviteten, at holde den udøvende magt på linje med dens umiddelbare opgave (gennemførelse af love), at afsløre spild, bureaukrati, svig og korruption, beskyttelse af borgerrettigheder og frihedsrettigheder osv. Det er en omfattende overvågning af hele den politiske gennemførelse. Dette er i øvrigt ikke noget, der hører fortiden til, det er opstået fra forfatningens begyndelse og er en ubestridt del af det geniale system af checks and balances .

Forfatningen kender ikke dette "Kongressens tilsyn" med så mange ord, men det er meningen, at det skal være en ufravigelig forlængelse af den lovgivende magt: Hvis man er bemyndiget til at lave love, skal man også være bemyndiget til at kontrollere, hvad der sker i forbindelse med deres gennemførelse. Det er en selvfølge i en administrativ cyklus.

Der har naturligvis været forsøg på at påvise ved en streng fortolkning af den amerikanske forfatning, at denne form for "implicitte beføjelser" ikke er i overensstemmelse med forfatningen. Den amerikanske højesteret har imidlertid altid afvist denne påstand. Dette er i overensstemmelse med præsident Woodrow Wilsons visioner, som anså denne parlamentariske overvågning for at være lige så vigtig som at lave love: "Lige så vigtigt som at lovgive er et årvågent tilsyn med administrationen". Alt dette i bevidstheden om, at den amerikanske forfatning i artikel I, afsnit 9, fastlægger de grænser, inden for hvilke den amerikanske kongres kan udøve de begrænsende beføjelser i afsnit 8.

Vi vil gerne henlede opmærksomheden på nogle specifikke bestemmelser i vores ændrede afdeling 2.

For det første, punkt a, beføjelse til at opkræve skatter og lignende. Dette er nødvendigt i Amerika for at betale gælden og "for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States". Vi har erstattet ordene i anførselstegn med "nødvendige for opfyldelsen af den garanti, der er fastsat i præamblen". Efter vores mening bør genereringen af den føderale myndigheds egne indtægter strække sig ud over betalingen af forbundets gæld og finansieringen af udgifter til forsvar og almen velfærd. Ud over den udtrykkelige henvisning til at kunne betale sin gæld mener vi, at det er vigtigt, at der her skabes en klar forbindelse til garantien i præamblen. Med andre ord, at en sådan beskatning også er til for at betale udgifterne "til frihed, orden, sikkerhed, lykke, retfærdighed, forsvar mod føderationens fjender, beskyttelse af miljøet samt accept og tolerance over for mangfoldigheden af kulturer, trosretninger, livsformer og sprog hos alle dem, der lever og skal leve på det område, der er under føderationens jurisdiktion".

Paragraf c kaldes "Commerce Clause" i den amerikanske forfatning. For Europas Forenede Stater vil anvendelsen af denne bestemmelse - bl.a. i lyset af indgåelsen af handelstraktater - være afgørende for Europas finansielle og økonomiske stilling. I denne henseende spiller spørgsmål som en skatteunion og internationaliseringen af euroen (se afsnit 3) en vigtig støttefunktion.

Explanation of Section 3

Section 3 is devoted to principled limits on the federal powers granted to Congress in Section 2 to protect individuals. This concise Section 3 on individual rights is sufficient in this draft Constitution. No more is needed. Indeed, Section I, Clause 3 of the draft states that the United States of Europe subscribes to the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (except for the inoperative principle of subsidiarity[1]) and accedes to the Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, concluded within the framework of the Council of Europe.

The first Clause of Section 3 gives the States the right to pursue their own policy on foreigners for a few more years. From the as yet unnamed year 20XX onwards, this will be federal immigration policy. And with that, the Federation of Europe will present itself as a Federation that welcomes foreigners under certain conditions, instead of using bureaucratic and hostile policing mechanisms and legal constructions aimed at defence to keep citizens from other continents out of the Federation, or to expel them. The United States of Europe can still use tens of millions of active, enterprising peoples to enrich its cultural diversity, strengthen its economy and cope with its shrinking population. This requires a policy[2] that organises immigration for the benefit of the Federation and the immigrant. European policymakers can take inspiration from the policies of Federations such as Australia, Canada, and the United States.

Explanation of Section 4

According to Clauses 1 and 2 of this Section, neither the States of the Federation, nor the Federation itself, may introduce or maintain regulations which restrict or interfere with the economic unity of the Federation. Again, powers not expressly assigned to Congress by the Constitution in Article III, Section 2 rest with the Citizens and the States. This is the other side of the coin called 'vertical separation of powers'. Nevertheless, in America it was considered useful and necessary at the time not only to place limits on Congress in their Article I, Section 9, but also to remind the States that their powers are not unlimited. To this end, their Article I, Section 10 (our Article III, Section 4) stipulates what the States may not do.

Clause 3 imposes the same limitation on the legislative power of the States as that of the Federation, contained in Section 3(3), in order to maintain legal certainty, not to affect the exercise of judicial power and to safeguard rights of Citizens in force or enforced. It is also important, a subject that has often been addressed by the US Supreme Court, that States may not legislate to override contractual obligations. Legal certainty for contractors and litigants is of a higher order than the power to declare a contract or a court decision ineffective by law.

In Clause 4, the provision that none of the member States of the Federation may create its own currency (taken from James Madison's Federalist Paper No 44) is a clear warning to some EU Member States considering returning to their own former national currencies. Nevertheless, states are allowed to issue bonds and other debt instruments to finance their deficit spending. In other words, we are proposing to create a financial system similar to that of the USA.

Clause 5 states that export and import duties are not within the competence of the States unless they are authorised to do so. They may, however, charge for the expenses they incur in connection with the control of imports and exports. The net proceeds of permitted levies must fall into the coffers of the Federation. This matter is likely to have a high place on the agenda of the previously recommended six Senators (without voting rights) delegated by the ACP countries to the European Senate.

Clause 6 emphasizes once again that defence is a federal task. On the understanding that the European Congress may decide that a member state shall accommodate on its territory a part of that federal army and keep it ready to act in case of emergency.

Explanation of Section 5

In this Section 5 we have included a number of additional rules to combat political corruption[3]. Because gigantic sums of money are spent on election campaigns in America, there is a saying: "Money is the oxygen of American politics". In our federal constitution for the United States of Europe, Article III, Section 5 contains Clauses justifying the adage: 'Money should not be the oxygen of European politics'.

This is our description of Articles I-III of the United States of Europe. We have stuck as closely as possible to the text of the US Constitution. It is therefore conceivable that words or phrases - vital for a federal Europe - may be mistakenly missing or incorrectly worded. Or that we are regulating things here that are not necessary in the envisaged European federal context. That is why this - like the rest of our draft Constitution - is open to addition and improvement by the Citizens' Convention.

The following Articles IV-X are partly taken from the original US Constitution itself, partly supplemented and improved by texts from the amendments subsequently added to it by Congress. Here too we allow ourselves to improve the readability of the structure of the American Constitution by separating the organisation of the executive branch from the duration and vacancy of the (vice-)presidency.

[1] The principle of subsidiarity is also not mentioned in the Preamble because subsidiarity coincides with federal statehood. This has already been explained.

[2] That policy will say goodbye to Frontex, the European Border and Coastguard Agency. The way in which the European Union has allowed that agency to evolve, in terms of its powers, personnel, procedures and weapons, into a defence mechanism with no democratic control and no scrutiny by human rights organisations, thus becoming the playground of industrial lobbyists, may well evolve in the greatest anti-humanitarian crime of the 21st century.

[3] Clauses 3-9 of Article III were added by Leo Klinkers, taken from Charles Hugh Smith, ‘10 Common- Sense Amendments to the US Constitution’, 21 February 2019.

Artikel III - Den lovgivende magts beføjelser

Afdeling 1 - Legislative procedure

- Both Houses have the power to initiate laws. They may appoint bicameral commissions with the task to prepare joint proposal of laws or to solve conflicts between both Houses.

- The laws of both Houses must adhere to principles of inclusiveness, deliberative decision-making, and representativeness in the sense of respecting and protecting minority positions within majority decisions, with resolute wisdom to avoid oligarchic decision-making processes.

- The House of the Citizens has the power to initiate legislation affecting the federal budget of the European Federal Union. The House of the States has the power - as is the case with other legislative proposals by the House of the Citizens - to propose amendments in order to adjust legislation affecting the federal budget.

- Each draft law is sent to the other House. If the other House approves the draft, it becomes law. In the event that the other House does not approve the draft law, a bicameral commission is formed - or an already existing bicameral commission is appointed - to mediate a solution. If this conciliation produces an agreement or a proposal of law, this is subject to a majority vote of both Houses.

- Any order or resolution, other than a draft law, requiring the consent of both Houses – except for decisions with respect to adjournment – are presented to the President and need his/her approval before they will gain legal effect. If the President disapproves, this matter will nevertheless have legal effect if two thirds of both Houses approve.

Section 2 - The Common European Interests

- The European Congress is responsible for taking care of the following Common European Interests:

- (a) The livability of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies against existential threats to the safety of the European Federal Union, its States and Territories and its Citizens, be they natural, technological, economic or of another nature or concerning the societal peace.

(b) The financial stability of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies to secure and safe the financial system of the Federation.

(c) The internal and external security of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on defence, intelligence and policing of the Federation.

(d) The economy of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on the welfare and prosperity of the Federation.

(e) The science and education of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on the level of wisdom and knowledge of the Federation.

(f) The social and cultural ties of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on preserving established social and cultural foundations of Europe.

(g) The immigration in, including refugees, and the emigration out of the European Federal Union, by regulating immigration policies on access, safety, housing, work and social security, and emigration policies on leaving the Federation.

(h) The foreign affairs of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on promoting the values and norms of the European Federal Union outside the Federation itself. - The Federation and the Member States have shared sovereignty concerning those Common European Interests. The European Congress derives its powers in relation to these Common European Interests from powers that the Member States of the Federation entrust to the federal body through a vertical separation of powers. This implies that new circumstances may lead to a decision by the European Congress to increase or decrease the list of European Common Interests.

- Appendix III A, being integral part of this Constitution but not subject to the constitutional amendment procedure, regulates the way the Member States decide which powers to entrust to the federal body. It also regulates the influence of the Citizens on that process.

Section 3 – Constraints for the European Federal Union and its States

- No State will introduce state-level policies or actions that can threaten the safety of its own Citizens, or of Citizens of other Member States.

- No taxes, imposts or excises will be levied on transnational services and goods between the States of the European Federal Union.

- No preference will be given through any regulation to commerce or to tax in the seaports, air ports or spaceports of the States of the European Federal Union; nor will vessels or aircrafts bound to, or from one State, be obliged to enter, clear, or pay duties in another State.

- No State is allowed to pass a retroactive law or restore capital punishment. Nor pass a law impairing contractual obligations or judicial verdicts of whatever court.

- Ingen stat vil udstede sin egen valuta.

- No State will, without the consent of the European Congress, impose any tax, impost or excise on the import or export of services and goods, except for what may be necessary for executing inspections of import and export. The net yield of all taxes, imposts, or excises, imposed by any State on import and export, will be for the use of the Treasury of the European Federal Union; all related regulations will be subject to the revision and control by the European Congress.

- No State will have military capabilities under its control, enter any security(-related) agreement or covenant with another State of the Federation or with a foreign State, and can only employ military capabilities out of self-defense against external violence when an imminent threat requires this, and only for the duration that the Federation cannot fulfil this obligation. The military capabilities that are used in the above-mentioned situation are capabilities that are stationed on the State’s territory as part of that federal army.

Section 4 – Constraints for the European Federal Union

- No money shall be drawn from the Treasury but for the use as determined by federal law; a statement on the finances of the European Federal Union will be published yearly.

- No title of nobility will be granted by the European Federal Union. No person who under the European Federal Union holds a public or a trust office accepts without the consent of the European Congress any present, emolument, office, or title of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince or foreign State.

- Intet personale, betalt eller ulønnet, fra regeringen, offentlige kontrahenter eller enheder, der modtager direkte eller indirekte finansiering fra regeringen, må sætte foden på fremmed jord med henblik på fjendtligheder eller handlinger til forberedelse af fjendtligheder, medmindre det er tilladt i henhold til en krigserklæring fra Kongressen.

- No person or entity, whether living, robotic or digital, may contribute more than one day's wages of the average laborer to a person seeking elected office in a particular election cycle, in currency, goods, services or labor, whether paid or unpaid. Anyone seeking an elected position that accepts more than this amount in any form, and anyone who seeks to circumvent this statutory limit on campaign contributions, will be barred from holding office for life and will serve a minimum term of imprisonment of five years.

- No person or entity that has directly or indirectly received funds, favors, or contracts from the government during the last five years may contribute to an election campaign under the sanctions described in clause 6. In addition, any entity seeking to circumvent this limitation shall be fined five years of its annual turnover, payable on conviction.

- Ethvert bidrag, hvad enten det er direkte eller indirekte, i form af kontanter, varer, tjenesteydelser eller arbejdskraft, betalt eller ulønnet, til en person, der søger et valgt embede, skal offentliggøres senest 48 timer efter modtagelsen. Bidraget fra hver enhed skal være forsynet med navnet på den eller de personer, der er ansvarlige for ledelsen af enheden. En enhed, der forsøger at omgå denne begrænsning, straffes med en årlig bøde på fem år, der skal betales ved domfældelse.

- Ingen person må bruge mere end en måned af gennemsnitsarbejderen gennemsnitlige månedsløn på sin egen kampagne til et valgt embede. Enhver, der ønsker at omgå denne lovbestemte grænse for kampagnebidrag, vil blive udelukket fra at bestride et embede på livstid og vil blive idømt en straf på mindst fem års fængsel.

- Ingen statsansat må acceptere en stilling i en privat virksomhed, der har accepteret statslig finansiering, begunstigelser eller kontrakter i en periode på ti år efter at have forladt det statslige embede inden for de seneste fem år.

- Alle offentlige institutioner og agenturer og alle enheder eller personer, der direkte eller indirekte har modtaget offentlig finansiering, begunstigelser eller kontrakter, skal underkastes en uafhængig revision hvert fjerde år, og resultaterne af disse retsvidenskabelige revisioner skal offentliggøres på datoen for deres udstedelse. Enhver enhed, der forsøger at omgå eller undgå dette krav, vil blive idømt en bøde på fem års fængsel, der skal betales i tilfælde af en domfældelse. Enhver person, der forsøger at omgå eller undgå dette krav, skal afsone en fængselsstraf på mindst fem år.

Forklaring til afsnit 1

Clause 1 entitles both Houses of the European Congress to make initiative laws. Not the President and the Ministers of his Cabinet. These executives do not even act in the Houses. This strict separation of legislative and executive power guarantees the autonomy of the European Congress in its core task: the drafting and final approval of federal laws.

Clause 2 is a rather revolutionary text. Laws - with commandments and prohibitions - are the strongest instrument by which a government determines the behavioural alternatives of its Citizens. Citizens who believe that laws do not sufficiently consider the requirement of inclusiveness, deliberative decision-making, and representativeness in the sense of respecting and protecting minority positions within majority decisions, with resolute wisdom avoiding oligarchic decision-making processes can challenge this up to the highest court. The Federal Court of Justice has the power to test laws against the Constitution. In this Clause 2, therefore, lies a fundamental aspect of direct democracy: citizens have the right to challenge the correctness of a law before the highest court.

Clause 3 gives the exclusive power to the House of the Citizens to make tax laws. Unlike legislation in the general sense, the House of the States therefore does not have that power. However, that House may try to change those tax laws through amendments. The reason for declaring only the House of the Citizens competent to take an initiative in this regard is based on the consideration that 'groping in the purse of the citizens' is solely and exclusively at the discretion of the delegates of those Citizens.

The House of the Citizens thus decides what type of federal taxation will take place: income tax, corporation tax, property tax, road tax, wealth tax, profits tax and/or value added tax. Or perhaps it will leave those types of tax to the jurisdiction of the States and creates only one new type of tax under the name Federal Tax, provided that States' taxes are simultaneously reduced or abolished to prevent this Federal Tax from being imposed at the expense of the Citizens. The Constitution says no more about this because it is a subject for the politically elected.

Clause 4 excludes the President's involvement in the legislative process of both Houses. The US Constitution gives the President the power to veto a draft law, but then a complicated process follows between the President and both Houses to agree or disagree. We do not consider it desirable for the President, as leader of the Executive Branch, to participate in law making, nor in interfering in a possible dispute between the two Houses. We provide the establishment of a mediating bicameral commission in case both Houses cannot work it out together.

Clause 5 gives the President a say in legislative matters of a lower level than a law.

Forklaring til afsnit 2

If one sees the Preamble as the soul of the Constitution, then Section 2 of Article III is its heart. It mixes procedural provisions with substantive issues and the way they are to be dealt with partly by the Federation and partly by the Member States.

The end-means relationships of the Constitution

Building a federation is mainly a matter of structure and procedures. It is not about substantive policy. There is no such thing as federalist policy, for example, in the sense of federalist agricultural policy. There are, however, the policies of the federation. But their content is not determined by the fact that it has a federal form of organisation but by the political views and decisions of the members of the House of the Citizens, of the States and of the Federal Executive. The Federation itself has no political colour. It is not left-wing; it is not right-wing, is neither progressive nor conservative. It is a safe house for all European Citizens, regardless their political, social, religious belief. A structure with procedures and guarantees that are geared as much as possible towards taking care of Common European Interests. In other words, interests that individual Member States can no longer take care of on their own.

Section 2 shows the list Common European Interests in relation to substantive subjects for which the Federal Authority needs powers to look after those interests. Because this federation is built on the principles of centripetal federalizing (by building from the bottom up the parts create the whole) the Member States shall determine for which Common European Interests they are entrusting which powers to the federation. This is the most important condition for preventing the federation from developing into a superstate. Federations that are built top down (centrifugal federalisation: a central government creates parts) have the characteristic that there will always be centralist aspects in the federation, with the risk of weakening the classical federal structure that aims to ensure that the parts always remain autonomous, independent, and sovereign.

Thus, the powers of the federal body come from the Member States, not in the sense of transferring or conferring, but in the sense of entrusting: the Member States make some of their powers dormant, as it were, so that the Federation can work with them to realise the Common European Interests. That is the socalled vertical separation of powers between the Member States and the Federal Authority, leading to shared sovereignty between the two.[1]

[1] The vertical separation of powers is the same as establishing subsidiarity. In other words, nowhere in a well-designed federal constitution is there a sentence that points to the principle of subsidiarity for the simple reason that the concepts of ‘vertical separation of powers’ and ‘subsidiarity’ coincide. See for more information the paragraphs 4.2.5, 4.2.8, 5.2, 5.3.2, 5.4 of the aforementioned Toolkit: https://www.faef.eu/wp-content/uploads/Constitutional-Toolkit.pdf.

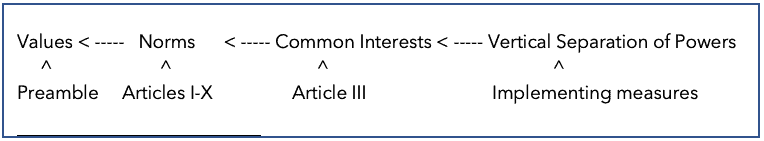

This requires a return to the passage on ‘Values and Interests’ in the General Observations of the Explanation to the Preamble. The Preamble to a federal Constitution is about values. The values are the objectives to be achieved through the deployment of Articles I to X. These articles contain the norms – read means – by which the values – read objectives – must be realised. The composition of a Constitution is thus a balanced relationship between values and norms or – in other words – between ends and means.

Interests on the other hand – better the Common European Interests of Europe, to be taken care of by the Federal Authority – are part of a second ends–means relationship. They are the means to realize the norms. And they are cared for and secured through the Vertical Separation of Powers between the Federal body and the Member States. So, that is a third means to end relationship.

Note that these three ends–means relationships are part of the ingenious system of checks and balances and require such attention that the ends are clear, that the means are clear and that the means can realise the ends. The arrows in the diagram – from right to left - show the means to end relations:

The FAEF Citizens’ Convention started the process of improving a provisional Constitution text with the perception that there are Values and Common European Interests; and that we can achieve (much) more through cooperation. Realization of these Common Interests are the objectives of forms of cooperation between the Member States and a Federal Authority. By expanding the scope, scale, and depth of the collaboration, it becomes possible to define those Common Interests in terms of means to fulfill the Norms and the Norms to fulfill the Values. These Values are understood as the foundation of the Federation, and as the ultimate objectives to be achieved. They have become the objectives in terms of the ‘what’ and indicate the desired direction (of development) for the Federation.

The Articles I - X concern principles for the organization of the Federation (structure and process) - the ‘how’ - and reflect (must be consistent with) the Values. The Articles can be considered Norms. i.e. rules and expectations (of ‘behavior’) that can be enforced. They are the means to fulfill the Values.

The Common Interests are the ‘where’. They can be considered ‘result areas’ that are established with a centripetal approach to federalization (bottom-up, minimalistic/cautious approach). These result areas are the more concrete issues/challenges where the Federation can provide added value for the Member States and the Citizens of the federation. The ‘field of activity’ of the Federal Authority is defined through the Common European Interests, that are identified by the Member States and its Citizens.

The Vertical Separation of Powers defines the content, the depth and the scope of the Common European Interests and is the beginning of the series of goal-means relationships. Anything that goes well - or perhaps not well - in the process of the vertical separation of powers by which Member States entrust powers to the Federal body will positively or negatively affect the meaning and value of the Common Interests. That, in turn, will affect the quality of the Norms and, in turn, that will affect the quality of achieving the Values. Thus, the success of the vertical separation in a good cooperative effort ultimately determines the success of what the Federation aims to achieve with the Values of the Preamble.

The Clauses of Section 2

Clause 1 lists the Common European Interests. This is the fulcrum of a federal Constitution. The only reason to make a centripetal federation is that States realise that they can no longer look after some interests on their own. They then jointly create a Federal body and ask that body to look after a small set of common interests on their behalf and of their Citizens.

Clause 1 lists the name of the Common European Interests. This gives a good idea of what these interests mean. For a better idea of their content, see Appendix III A. The Appendix describes the procedure for the vertical separation of powers which gives indications of the subjects of policies that are entrusted to the care of the Federal authority.

Clause 2 explains what a centripetal federation is: the parts create a whole, a centre, which is empowered by the parts to look after common interests that individual States can no longer look after on their own. Although the list of Common European Interests is exhaustive, Clause 2 offers a window for increasing or decreasing it if new circumstances warrant. Naturally, this must be done via the procedure of Appendix III A and of the procedure to amend the Constitution. New circumstances can be: a new insight in the meaning of the values and norms of the constitution; a new insight in the meaning of Common European Interests that affect at least three states and have the potential to escalate to other states; the realization that the scale of new circumstances requires a uniform, efficient federal response.

Clause 3 refers to Appendix III A that regulates the procedure of the vertical separation of powers. See the end of this Explanation on Article III.

More powers than the ones in Section 2

It is to be expected that the practice of the European Federal Union will show that the Houses of the European Congress - just like those of the US Constitution - feel that they do not have enough powers with the exhaustive Common European Interests mentioned in Section 2. A system of 'additional powers' will undoubtedly develop. An expansion of the complex of powers of both Houses that may be at odds with the intentions of the Constitution. One should think here of the following - potential - developments.

One of the most important is called 'Congressional Oversight'. This oversight - organised mainly through parliamentary committees (both standing and special), but also with other instruments - concerns the overall functioning of the Executive branch and Federal Agencies. The aim is to increase effectiveness and efficiency, to keep the executive in line with its immediate task (execution of laws), to detect waste, bureaucracy, fraud and corruption, protection of civil rights and freedoms, and so on. It is a comprehensive monitoring of the entire policy implementation. This, by the way, is not something of the recent past in the US. It arose from the inception of the Constitution and is an undisputed part of the ingenious system of checks and balances. It will undoubtedly develop in the same way in Europe.

The Constitution does not know this 'Congressional Oversight' in so many words, but it is supposed to be an inalienable extension of the legislative power: if you are authorised to make laws, you must also be authorised to control what happens in their implementation. It is self-evident in an administrative cycle. Of course, there have been attempts to demonstrate with a strict interpretation of the US Constitution that this form of 'Implied Powers' is not in accordance with the Constitution. However, the US Supreme Court has always rejected this claim. This is in line with the vision of President Woodrow Wilson, who saw this parliamentary oversight as being just as important as making laws: "Quite as important as legislation is vigilant oversight of administration."[1]

[1] For more information on these issues, see Chapter 10 of the aforementioned Toolkit: https://www.faef.eu/wp-content/uploads/Constitutional-Toolkit.pdf.

Explanation of Section 3

Clause 1 restrains policies and actions that may be crushing for biodiversity or that, for example, polluting energy companies are opened or remain open in violation of climate agreements. This ban must make a positive contribution to energy and food availability and security.

According to Clauses 2 and 3 of this Section, neither the States of the Federation, nor the Federation itself, may introduce or maintain regulations which restrict or interfere with the economic unity of the Federation. Again, powers not expressly assigned to Congress by the Constitution in Article III, Section 2 rest with the Citizens and the States. This is the other side of the coin called 'vertical separation of powers'. Nevertheless, in America it was considered useful and necessary at the time not only to place limits on Congress in their Article I, Section 9, but also to remind the States that their powers are not unlimited. To this end, their Article I, Section 10 - our Article III, Section 3 - stipulates what the States may not do.

Clause 4 imposes the same limitation on the legislative power of the States as that of the Federation in order to maintain legal certainty, not to affect the exercise of judicial power and to safeguard rights of Citizens in force or enforced. It is also important, a subject that has often been addressed by the US Supreme Court, that States may not legislate to override contractual obligations. Legal certainty for contractors and litigants is of a higher order than the power to declare a contract or a court decision ineffective by law.

In Clause 5, the provision that none of the member States of the Federation may create its own currency (taken from James Madison's Federalist Paper No 44) is a clear warning to some EU Member States considering returning to their own former national currencies. Nevertheless, states are allowed to issue bonds and other debt instruments to finance their deficit spending. In other words, we are proposing to create a financial system similar to that of the USA.

Clause 6 states that export and import duties are not within the competence of the States unless they are authorised to do so. They may, however, charge for the expenses they incur in connection with the control of imports and exports. The net proceeds of permitted levies must fall into the coffers of the Federation. This matter is likely to have a high place on the agenda of the previously recommended six delegates of the House of the States (without voting rights) delegated by the ACP countries to the European House of the States.

Clause 7 emphasizes once again that defence is a federal task. On the understanding that the European Congress may decide that a Member State shall accommodate on its territory a part of that federal army and keep it ready to act in case of emergency.

Explanation of Section 4

In this Section 5 we have included a number of additional rules to combat political corruption. Because gigantic sums of money are spent on election campaigns in America, there is a saying: "Money is the oxygen of American politics". In our federal constitution for the United States of Europe, Article III, Section 5 contains Clauses justifying the adage: 'Money should not be the oxygen of European politics'.

Appendix III A - The procedure for the vertical separation of powers

By ratifying the Constitution, the Citizens adopt the limitative and exhaustive list of the Common European Interests. The question, however, is: how can one properly determine which powers are necessarily needed to enable the Federal Authority to do its job? For that, a procedure is needed. A procedure of debate and negotiation within which the Citizens (direct democracy) and the States play a prominent role. For this purpose, Clause 3 refers to Appendix III A which is an integral and therefore mandatory part of the Constitution, but for any future adjustment it is not subject to the amendment rules of the Constitution.

If the Constitution is ratified by enough Citizens to establish the Federation

the limitative and exhaustive list of the Common European Interests will be established. The meaning of this is: the Citizens have spoken; that list is non-negotiable during the debate and negotiation necessary to determine which powers should be entrusted – by means of that vertical separation of powers - to the Federal Authority, to enable the Federation taking care of the Common European Interests.

Let us repeat once again that the Member States retain their sovereignty in the sense that they do not transfer or confer parts of their sovereignty to the federal body and would thus lose those sovereignty. What they are doing is entrusting some of their powers to the federal body because that body can look after Common European Interests better than the Member States themselves. Thus, the Member States make their relevant powers dormant. The effect is shared sovereignty.

The vertical separation of powers will always be a matter of debate and will sometimes require adjustment. That is why the outcome of the debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers will be another Appendix to the Constitution: Appendix III B. The Appendix III A on the procedure of the process of the vertical separation of powers and the future Appendix III B, containing the result of that procedure, are integral parts of the Constitution but might be adjusted during the years without being subjected to the constitutional amendment procedure. This is to prevent that any necessary adjustments of the vertical separation will force to amend the Constitution itself.

On the basis of three principles, the founding fathers of this Constitution lay down the following procedure for determining the vertical separation of powers.

Principle 1 – from bottom to top

It would be a severe system error to arrange the allocation of powers from top to bottom. Wherever possible in the construction of a federal state, one should always work from the bottom up. That is a ‘commandment’ of the centripetal way on which this federal Constitution is based. This requires asking the Member States which parts of their complex of competences they wish to make dormant, so that the federal body can dispose of them to take care of the Common European Interests.

One must be careful not to think in terms of decentralization. Decentralization is ‘moving from top to bottom’: the center shares parts of its powers with lower authorities. This does happen in federal states that are centrifugally built: a centre creates parts. But the effect of such a course of action is that there will always remain unitary/centralist aspects. If countries such as Spain and the United Kingdom were to decide to further decentralize their already existing devolved autonomous regions into parts of a federal state, they would run the risk of creating a relatively imperfect federal state as well.

Principle 2 – debate and negotiation on Common European Interests

If the electorates of some European states ratify the Constitution by a majority, and if their parliaments follow the will of their people, the debate and negotiation on the powers that the Member States entrust to the Federation starts. This process is as follows:

a) Internal deliberation by individual Member States

Each Member State has two months to prepare a document in which it puts forward proposals on the powers it wishes to entrust to the Federal body. In total, they draft one document for each Common European Interest. In doing so, they give an insight into the way in which they think the Federal body should be vested with substantive powers and material resources. A Protocol establishes the requirements that the documents must meet in order to be considered, among which the organization of the way Citizens participate in that process (direct democracy). The central requirement is that they must deal with the representation of Common European Interests that a Member State cannot (or can no longer) represent in an optimal manner itself.

b) Aggregation of the documents

Under the leadership of FAEF, a Transition Committee is created beforehand to regulate the transition from the treaty-based to the federal system. This is where the Citizens come in as well: direct democracy. Led by FAEF, that Committee consists of (a) non-political Experts on the Common European Interests and (b) non-political Citizens. Point (a) is required for expertise. Point (b) is required to prevent the deliberation and decision-making on the vertical separation of powers from degenerating – as has been the case in the treaty-based intergovernmental EU-system since 1951 – into nation-state advocacy. The Transition Committee aggregates the documents of the Member States into a total sum of powers to be vertically separated, and the substantive and material consequences. Two months are available for this.

c) Final decision-making

The aggregated document is the agenda for a one week deliberation on each Common European Interest. Under the leadership of the Transition Committee, final decisions are taken on the best balanced allocation of powers from the Member States to the Federal body. This final document will be an integral Appendix III B of the constitution. After its implementation in the federal system practice will show when, why and how Appendix III A on the procedure of the vertical separation of powers needs improvements, so that the Appendix III B on the result of that procedure must undergo improvements as well.

d) The start of the construction of the federal Europe

The result of c) marks the beginning of the building of the federal Europe. Guided by a Transition Committee of Citizens, the Member States determine concretely how the federal body with a limited number of entrusted powers of the states should represent a limited amount of Common European Interests. It marks a barrier between the tasks of the federation and the fields in which the Member States remain fully autonomous and the federation cannot become a superstate.

Principle 3 - Debatable and negotiable subjects

Taking from the limitative and exhaustive list of Common European Interests of Section 2, Principle 3 contains non-exhaustive examples of topics on which the debate and negotiations may take place.

The formula is as follows:

The European Congress is responsible for taking care of all necessary regulations with respect to the territory or other possessions belonging to the European Federal Union, related to the following Common European Interests:

1. The livability of the European Federal Union,

by regulating policies against existential threats to the safety of the European Federal Union, its States and Territories and its Citizens, be they natural, technological, economic or of another nature, or concerning the social peace.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on all natural resources and all lifeforms, on climate control, on the implementation of climate agreements, on protecting the natural environment, on ensuring the quality of the water, soil, air, and on protecting the outer space;

(b) to regulate policies on preventing and fighting pandemics

(c) to regulate the policy on the safety and availability of food and drinking water;

(d) to regulate the policy on preventing scarcity of natural resources and dysfunctional supply chains;

(e) to regulate the policy on social security, consumer protection and child care;

(f) to regulate the policy on employment and pensions;

(g) to regulate the policy on health throughout the European Federal Union, including prevention, furthering and protection of public health, professional illnesses, and labor accidents;

(h) to regulate the policy on justice and on establishing federal courts, subordinated to the European Court of Justice.

2. The financial stability of the European Federal Union,

by regulating policies to secure and safe the financial system of the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on federal tax, imposts, and excises, uniformly in all territories of the European Federal Union, on the debts of the Federation, on the expenses to fulfill the duties imposed by this and on borrowing money on the credit of the Federation;

(b) to regulate the policy on installing a fiscal union;

(c) to regulate the policy on supervising the system of financial entities;

(d) to regulate the policy on coining the federal currency, its value, the standard of weights and measures, the punishment of counterfeiting the securities and the currency of the Federation.

3. The internal and external security of the European Federal Union,

by regulating policies on defence, intelligence and policing of the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on raising support on security capabilities, among which the policy on one common defence force (army, navy, air force, space force) of the Federation, on compulsory military service or community service, and on a national guard;

(b) to regulate policies in the context of external conflicts, policies on sending armed forces outside the territory of the Federation, on military bases of a foreign country on the territory of the federation, on the production of defensive weapons, on the production of weapons for mass destruction, on the import, circulation, advertising, sale, and possession of weapons, on the possibility of bearing arms by civilians;

(c) to regulate the policy on declaring war, on captures on land, water, air, or outer space, on suppressing insurrections and terrorism, on repelling invaders, and on fighting autonomous weapons;

(d) to regulate the policy on fighting cybercrimes and crimes in outer space;

(e) to regulate the policy on one federal police force;

(f) to regulate the policy on one federal intelligence service;

(g) to regulate fighting and punishing piracy, crimes against international law and human rights;

4. The economy of the European Federal Union,

by regulating policies on the welfare and prosperity of the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on the internal market;

(b) to regulate the policy on transnational production sectors like industry, agriculture, livestock, forestry, horticulture, fisheries, IT, pure scientific research, inventions, industrial product standards;

(c) to regulate the policy on transnational transport: road, water (inland and sea), rail, air, and outer space; including the transnational infrastructure, postal facilities, telecommunications as well as electronic traffic between public administrations and between public administrations and Citizens, including all necessary rules to fight fraud, forgery, theft, damage and destruction of postal and electronic information and their information carriers;

(d) to regulate the policy on the commerce among the Member States of the Federation and with foreign nations;

(e) to regulate the policy on banking and bankruptcy throughout the Federation;

(f) to regulate the policy on the production and distribution of energy supply;

(g) to regulate the policy on consumer protection;

5. The science and education of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on the improving the level of wisdom and knowledge within the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on scientific centers of excellence;

(b) to regulate the policy on transnational alignment of pioneering research and related education;

(c) to regulate the policy on the exclusive rights for authors, inventors, and designers of their creations;

(d) to regulate the policy on progress of scientific findings and economic innovations.

6. The social and cultural ties of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on preserving established social and cultural foundations of Europe.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on strengthening unity in diversity: “Acquiring the new while cherishing the old”;

(b) to regulate the policy on arts and sports with a federal basis.

7. The immigration in, including refugees, and the emigration out of the European Federal Union, by regulating immigration policies on access, safety, housing, work and social security, and emigration policies on leaving the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate policies on access – or denial of access - to the Federation, on security measures against terrorism and cybercrime related immigration, on mode of housing, employment, social security;

(b) to regulate policies on leaving the Federation.

8. The foreign affairs of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on strengthening the Common European Interests in the interest of global peace, social equality, economic prosperity, and public health.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on external cooperation to strengthen the policies on the foregoing Common European Interests.

(b) to define the means by which this common interest is promoted, e.g. through cooperation by States, especially concerning international trade (what is trade, with whom, under what conditions), developmental projects (what projects, with what partners, under what conditions), disaster relieve, projects to mitigate (the consequences of) climate change/global warming.

(c) to regulate policies to promote global federation.

To sum it up, correct thinking about federalizing is as follows

1. The Common Interests are the same as a Kompetenz Catalogue. It is a limitative and exhaustive list of concrete interests of a common European nature. They must be formulated in an abstract, generic way. In other words: the common interests must have a name. For example, 'The financial stability of the European Federal Union’.

2. Although the list of Common European Interests is exhaustive, the Constitution must provide for the possibility of adapting that list. The constitutional amendment procedure and that of Appendix III A shall apply.